Throttler: a Clojure library for rate limiting

Throttler is a little Clojure library I wrote a few weeks ago. As the name suggests, it limits the throughput or speed of something: either functions or core.async channels.

Here’s an example, straight from the library docs:

; A slow + function

(def +# (throttle-fn + 50 :second))

(+# 1 1) ; => 2

(time (dotimes [_ 200] (+# 1 1))) ; "Elapsed time: 4245.121 msecs (47/second)"The new function +# is equivalent to +, except that it runs at a measly 50

invocations per second.

The same goes for core.async channels. throttle-chan takes

an input channel and a goal rate, and returns an output channel that will emit

all messages sent to the input channel at the desired rate:

(def in (chan 1))

(def slow-out (throttle-chan in 10 :second))

(>!! in :hi) ; => true

(<!! slow-out) ; => :hi

(time

(dotimes [_ 50]

(>!! in :hi)

(<!! slow-out)))

; => "Elapsed time: 4893.739 msecs (10.2 msgs/sec)"This is equivalent to core.aysnc/pipe, but with a controlled output

rate.

Shared throttling

You can also limit the combined rate of a group of functions. Let’s say you want to throttle your own usage of an external service that you don’t control. You’d want to limit the number of API calls you make, making sure you stay within budget and/or your paid quota.

Here’s how you can throttle a whole API with Throttler:

; Create the api throttler with a goal rate

(def api-throttler (fn-throttler 1000 :day))

; Wrap all API methods with the same api-throttler:

(require [some.api :as api])

(def get-slow (api-throttler api/get-user))

(def put-slow (api-throttler api/put-user))

(def del-slow (api-throttler api/del-user))

(get-slow "RuPaul")

; -> { :name "RuPaul" :coolness ∞ :age "Don't you dare" }What happened here? We created a function throttler with a goal rate,

api-throttler, and applied it to the three functions in the API. Now you can

call the slow versions of any of the three functions, in any proportion, and

their overall rate will never be beyond what you specified.

The same can be achieved with channels, using the chan-throttler function.

Burstiness

Sometimes an average goal rate is not enough. Let’s say you want to make no more than 10,000 calls per day to a service. That would be around 0.11 calls per second, or about one call every 8 seconds.

If you haven’t called the service in a while, but suddenly you need to call it twice, the second request would have to wait for 8 seconds. So both of your calls would take no less than 8 seconds to finish! This is because, by default, Throttler enforces the goal rate with a millisecond granularity. At any moment you can pick a random time interval, and the number of calls in that time range will be at most the goal rate.

In this case though, we’d like to just keep ourselves under the maximum number of requests per day without caring too much about occasional request bursts.

What we need is a bursty throttler. The intuition is, if you haven’t used a throttled function or channel in a while, then you get “credits”, or “tokens”. Later, if you need to make some calls in quick succession, you use these credits and the calls execute right away. This is the main idea behind the Token-Bucket algorithm, which is how Throttler supports burstiness.

To create a bursty function or channel, you simply pass an extra argument stating how many tokens you are allowed to save up:

(defn bursty-api (throttle-fn api 10000 :day 1000)) ; Save up to 1000 unused tokensAbove, bursty-api may be called up to 1000 times in rapid succession,

provided there are enough tokens saved from previous periods of

quiescence.

Let’s see how a bursty function behaves in a benchmark. The function we’ll test simply prints out a timestamp:

(defn now [] (println (System/nanoTime)))

(defn now-bursty [] (throttle-fn now 10 :second 20))The throttled version of now will print at most 10 times per second, with

bursts of up to 20. Let’s exercise it with the following plan:

- Call

now-bursty30 times. This should take 3 seconds. - Sleep for 2 seconds. This should fill up the bucket with 20 tokens (10 per second, the average rate).

- Call the function 50 times. This should result in a burst of 20 messages, followed by 30 messages at 10 msg/second. In total all 50 calls should take about 3 seconds.

- Sleep for 1 second. This should save up 10 tokens.

- Call the function 50 more times. We should see a smaller burst of 10 messages, followed by 40 messages at 10 msg/second. This last phase should take 4 seconds.

In code, this looks like this:

(defn run [f]

(dotimes [_ 30] (f)) ; 1. Call fn 30 times

(Thread/sleep 2000) ; 2. Sleep for 2 seconds

(dotimes [_ 50] (f)) ; 3. Call fn 50 times

(Thread/sleep 1000) ; 4. Sleep for 1 second

(dotimes [_ 50] (f))) ; 5. Call fn 50 times

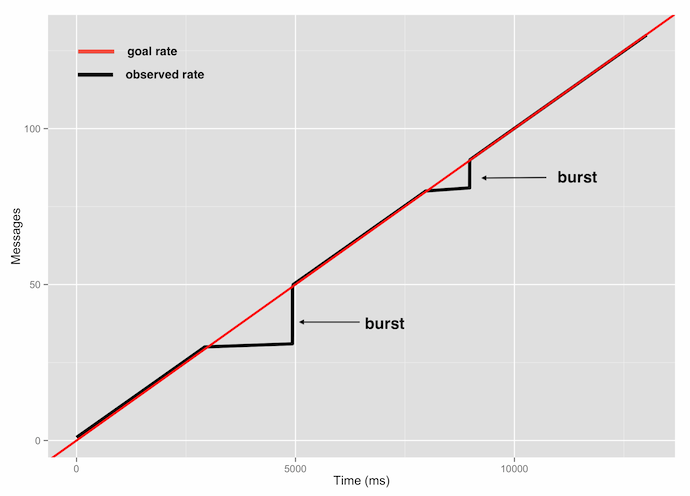

(run now-bursty)This is what the data looks like:

As you can see, the bursty function saves up tokens during inactive periods and is able to rapid fire after that. The invocations right after sleeping (steps 3 and 5) are executed at the maximum speed possible because the bucket has unused tokens at those points. This way, the overall goal is still honored.

Had we chosen a smaller bucket size, or slept for more time, we wouldn’t have been able to catch up entirely. Just how much burstiness is allowed is up to you.

Summary

Throttler makes it easy for you to flexibly control the throughput of functions and channels. It’s lightweight, precise over a very wide range of goal rates and fully asynchronous (it does not require dedicated OS threads nor it assumes that the wrapped function takes negligible time to run). And thanks to core-async, the implementation is quite short.

Enjoy!

Comments? Let me know on Twitter.